It is hard to find remains of Ainu art and culture in Japan, even within a stone’s throw of the hallowed grounds of Tokyo University. Nevertheless, if you are a dedicated art historian or folk art enthusiast, you don't need to look further, for here is a treasure house of artefacts kept in its original condition, housed in a historic mansion. With such an extensive collection, the museum rotates its entire exhibit several times a year, and I was fortunate to come face to face with some Ainu handicrafts during my visit. From the visitors, you can tell that this is a refined place, very much the domain of educated scholars and connoisseurs.

The museum was the brain child of Soetsu Yanagi, who was its first president in 1936. A keen collector of everyday crafts from all over Japan, he was a leading advocate of the Mingei Movement, and saw how these practical creations speak to the dignity of everyday life and of the place that it came from.

To the uninitiated, the layout of the museum resembles a glass menagerie of bric-a-brac, with one Ainu robe at the end of second floor, and two pieces of Ainu metal work at the other end of the same floor. However, there is a reason for the arrangement, with art forms like textiles in one room and metalwork in another.

My reason of visiting today was to inspect the Ainu robe, known as the Attu, which is made from the fibres of a Japanese elm tree. The Ainu hold these trees in high regard, seeing them as sources of wisdom. Their knowledge and traditions are passed from mother to daughter through the practice of making these robes, with the weaver sowing her prayers and protection into every weave. It is said that the geometric patterns act as a guardian angel, with Ainu believing that these ancestral robes have healing properties, so much so that young infants are swaddled in them to protect from disease.

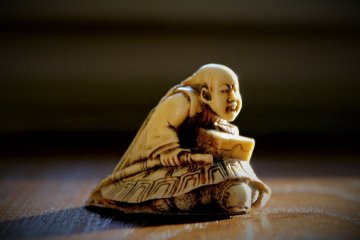

There is not much in terms of English captions or guided tours, but many of the exhibits speak for themselves with their creative genius, handicraft skills and reverence for nature and various religious beliefs found around the world. From time to time exhibits from around the world , such as Inca civilisation in Peru, or civilisations closer by, like the lion statues from Okinawa, gives you a sneak peek at how far and wide and universal our love for folk art is from around the world.

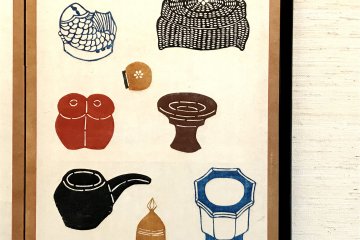

Folk art from different centuries and periods are also featured here, including the Edo and more modern periods. The pastel colours and almost childlike designs of teapots and other domestic, almost “farm house” objects look like the work of Taro Yamamoto, who has revitalised nipponga in his own way.

This museum is also a tribute to the many forward thinking collectors and patrons that have supported folk art in some way, through many generations. The story of Keisuke Serizawa’s collection, though not part of the permanent collection here, is one that spanned many generations. Born into a family who was especially fond of art, Keisuke collected miniature ema or votive pictures dedicated to shrines, as early as 1919. He, like Yanagi Soetsu, believed that in an age of industrialisation and fragmentation of the individual, human dignity is preserved by the living traditions of making and using objects that are whole . Folk Art is very much a practical art, of items of everyday use, with his designs adorning kimonos as well as illustrated books and match boxes, bring a connection to the contemporary world as well.

Patrons such as Yanagi and Serizawa personified the meaning of Mingei, folk art that is crafted for the common person.