Ogata Korin loved Noh. Actually, he was mesmerized by it. He sang, danced and painted Noh. It was as if the Noh masks had a trance-like effect on him. From the Tales of Ise, to the Noh play called “Iris”, I could imagine Korin dancing Noh in front of his screen painting of the same name.

Taro Yamamoto also loved Noh. He may have lived three centuries after Korin, but he walked the same laneways and sat on the same riverbank as Korin to watch nature display its fleeting beauty each season.

His painting, Sumida-gawa and Sakura-gawa, is a modern adaptation of two Noh plays of the same name. While these two plays share a similar theme, they also have very different endings. In Sumida-gawa, the mother has lost her child, apparently taken by a kidnapper. Driven by fear and despair, she began a lonely journey into the unknown to find her child. Arriving at Sumida River, she encounters a boatman who can tell her the truth. However, it is not the truth she was looking for. In Sakura-gawa, the mother arrives at Sakura River, framed by cherry trees in full bloom. With nervous anticipation, she scoops the cherry blossom petals floating on the river with a fish net, hoping to find her child, yet wishing that he won’t be found floating face down on the river.

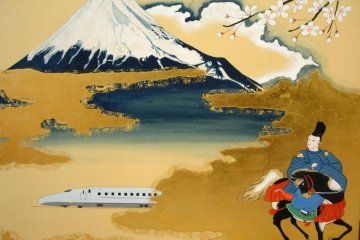

In the painting, you can see the two mothers standing side by side. With mask like expressions and stylized portrayals of nature, it looks like a traditional Rinpa style painting. However, if you look closely, Sumidagawa’s mother holds a kelpie doll instead of a phantom of her child. Sakura-gawa’s mother has a vacuum cleaner instead of a fishnet to scoop up Sakura petals, which symbolize her child, Sakurako. According to Yamamoto, a Nipponga painting like this is a modern take on Rinpa art, something that is both humorous and unexpected.

On the other hand, I feel the inclusion of everyday, contemporary objects in a stylized Neo-Rinpa style painting gives them a sense of other worldliness, as if they become immortalized in the tales of the Noh world. The juxtaposition of a kimono-clad woman with a stiff Noh mask-like face with a vacuum cleaner pokes humor and delight. To me it is a little like seeing a little girl in ponytails, barely seeing over the dashboard, but driving a black pumped up monster of a sports car. It makes a statement about how we see things today, but at the same time, it shows how Yamamoto uses kaigyaku, a particular type of Japanese dry humor, to great effect.

Another feature of Noh is the use of fans to communicate with the audience in ways that words cannot express. Yamamoto takes this theme further, by communicating the reality and images of red and white waves, which are on closer inspection, are not Rinpa motifs, but Coca Cola waves. Who knows, in a hundred years’ time Nipponga may become as well known as Rinpa.

Imura Art Gallery showcases a variety of up and coming artists, especially those with a close connection to Kyoto. Revolving exhibitions include Yasuko Iba, Jumpei Ueda, Etsuko Kawamura, Hideki Kimura, and Yu Kiwanami, bringing an eclectic mix of wit, science fiction, pop art, and childlike fantasy.