Chiharu Shiota once said: "The mind and body became detached from each other, and I am no longer able to put a stop to these uncontrollable emotions. I lay my own body out in scattered pieces and have a conversation with it in my mind. Somehow, I understand that this is what the act of connecting my body to these red threads is about. The act of expressing these emotions and giving them a form always also involves the soul being destroyed." These are the words that came into my mind as I met the puppet makers of Awaji. “When I made my first puppet mask, I was so excited I was practically shaking. These days I perform and know deeply the connection between art and craft.”

Unlike other forms of Japanese theatre, a puppet does not speak, and so the months spent carving the facial features, the movements of the eyes, ear lashes and mouth are key to telling the story. There is no greater appreciation in the puppeteer for bringing a piece of wood to life than in the person who created the puppet.

Puppets and its meaning in Japan

The ancients thought that spirits descended from the forests and mountains, and so used wood to welcome these spirits in their village festivals. Priests sought after the advice of these spirits through the manipulation of wooden sticks, the predecessors of puppets, and so it is no wonder that the wood from which puppets were carved, was held in awe.

From its debut in the eleventh century to its portraits of the working classes in Dotonbori in the seventeenth century, puppet theater has a sense of relatability and intimacy, highlighted by its development outside the imperial court and its oral traditions, with each performer adding to the richness of the composition of the play and the articulation of the music.

There are three kinds of stories featured, jidaimono Period dramas, sewamono everyday stories of the common people, and journey or philosophical stories. As such, there is a connection between the natural and supernatural worlds. For example, the Gabu can transform from a beautiful maiden to a ghost or monster, while a Tamamonomae can transform into a fox. There are also the Songoku, the Monkey King on a pilgrimage to the west which inspired the television series, Monkey Magic. Then there is a jealous woman with hidden horns, which can pop out in a fit of anger. With over 100 plays in his repertoire, Chikamatsu Monzaemon is dubbed the Shakespeare of Japanese theatre.

Bunraku or Puppet Theater

While the term Bunraku and Japanese puppets seem interchangeable, the term Bunraku wasn’t used until the nineteenth century, as Bunraku is basically an Osaka form of ningyō jōruri (人形浄瑠璃). Ningyo is a word covering both puppets and dolls, while joruri is when the narration or chanting of the ballads and the playing of shamisen come together to create the drama. The narration or chanting, along with the music is key, as they help to express the feeling of the puppets who don’t speak.

Osaka vs Awaji - Professional vs Amateur

While Osaka has professional actors in National Bunraku Theatre, it was influenced by amateurs. In the early 1790s, Uemura Bunrakuken from Awaji Island set up a small theatre in Osaka, whose efforts in reviving a dying art led to the creation of the Bunraku Theatre in 1805. Its success led to its acquisition by Shochiku, a theatre company that is now better known for producing films featuring directors like Yasujirō Ozu, Takeshi Kitano, and Akira Kurosawa, showing the cross-fertilization of ideas between professional filmmaking and amateur Bunraku productions.

UNESCO Heritage – from humble roots to national living treasures

Bunraku’s contribution throughout time, and to modern entertainment, has been recognized by UNESCO, which named it as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2003.

However, it was not always an exalted art form. Originally associated with kugutsu-mawashi, or itinerant puppeteers, they were like minstrels operating at the fringes of society. The Kairaishi-ki in the eleventh century tells of these troupes as nomads who live in tents and travel on horseback, performing mimes, puppet shows, and fight scenes, mesmerizing the village audiences with their circus-like spectaculars.

On Awaji Island, there is a saying, "The play starts in the morning, and the lunch box starts in the evening." When the puppet show came, it was the pinnacle of luxury to watch the puppet show outside on a sunny day, after preparing boxes filled with delicious treats from the night before.

While they have moved from smaller open-air performances to the grand affairs of a purpose-built theatre, the oral and musical traditions, much like Kamishibai, show how alluring a live act can be for many generations, connecting fantasy and spiritual worldviews in Japanese literature and performance arts. The concept of Yugen, which means profound mystery, is one that is articulated in both Noh and Bunraku puppetry, a way of expressing the mystery of human existence.

Awaji Puppet Theatre today

The Awaji Puppet Theatre was formed in 1964 and is a worthy inheritor of several centuries of Awaji puppetry, having in the past the patronage of the feudal lord of Tokushima.

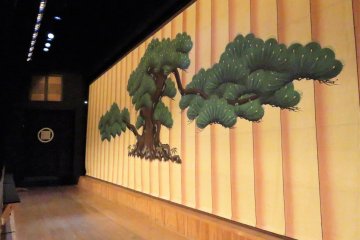

Unlike the earlier days, you don’t need all day or pack your lunch the night before to watch it, as they have multiple shows a day which are for a much shorter period. What they have inherited from the past is the running of daytime shows, allowing day-trippers from Kobe or Osaka to visit. There is also a backstage tour which reinforces the intimacy of Awaji Island, as you can see the puppets close up, as well as the ropes that pull the sliding screens in rapid succession. While the shows are in Japanese, there are audio guides and explanations in English as well.