If we deconstruct the phrase “moving picture” into its two elements, we can begin to understand the essence of Noh.

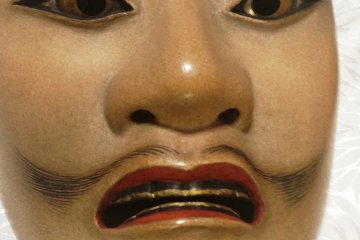

The medium of visual art is represented by paintings. Whether it is the color, the light and shade, or the composition, these are the sub-elements that make or break its impact. In Noh, just a slight tilt of the mask is sufficient to change a character’s mood, from jovial to sullen. In many ways these masks bring together the art forms of painting and sculpture, and with every movement of the chisel, the sculptor can be likened to god in creating the personality of the mask.

The other element focuses on movement. The performer behind the mask brings Noh to life, and the combination of movement, chanting and music creates an otherworldly experience. Everything in their folklore, from the wonders of the cosmos to stories of creation and destruction, is given life when these masks are used, some for hundreds of years. The Ko-omote mask of a young lady, named the “snow” mask, was a favorite of Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Now entrusted to the Kongo school these masks aren’t museum pieces, but become more lifelike the more they are used.

Today’s audience may be disappointed when they see Noh for the first time, as it can appear incomprehensible. Some scores have an almost spiritual dimension; one that would wake up the dead and take the living to a place they didn’t know existed.

Noh plays are an abstract form of performance that blends dance, music and acting, all into one spiritual whole. Like many abstract forms of expression, there is a Zen-like emptying of yourself, the noise that goes on in your mind when you watch, and indeed, participate in Noh. It is somewhat akin to viewing the stone garden at Ryoanji and either trying to work out what the stones represent, or not try to work it out at all.

Fans of early twentieth century film can see its influence on Ozu Yasujiro and Mizoguchi Kenji. In Tokyo Story, the almost still shots of the salarymen in the darkened scenes of the izakaya, with one or two lights giving a chiaroscuro effect is almost Noh-like in its essence. From Kabuki to Anime and even modern advertising, Noh is ever present in Japanese life.

One of my most memorable experiences was watching Takagi Noh in the garden of Osaka Castle. It was just after sunset on a balmy May evening, and with the castle lit up against the pinkish sky and a glass of wine in hand, it had a picnic like atmosphere. Of course, purists may prefer to see Noh inside the specially constructed theatre, its dimensions and unadorned simplicity adding to the force of the drama.

Noh in its current form was perfected in the Muromachi Period (1394 – 1466) by Kanami and his son Zeami, though the tradition of theatre masks date longer than that. Zaemi quoted the Kojiki ancient chronicles in which “The whole of the great Takama Plain was moved and all the eight million deities laughed.” As this was performance for the gods, there is an affinity with the plays of Ancient Greece, and it was said that the earlier Gigaku masks were influenced by the Greek tragedy masks coming to Japan via the Silk Road. There are around two hundred Gigaku masks still in existence today, with the oldest ones dating from the 7th century.

Originally there were between 50 to 70 different kinds of masks, but if you were to study in detail, you will soon realise that there are hundreds of different masks used today.

At this modest building off the tourist map in Osaka, you can see them making the same masks that were used a few hundred years ago. The teacher would make the first mask, after which they use the original to carve each mask by hand from a block of cypress or Hinoki wood. It could take up to eight weeks to finish a mask. Once finished, the lady at the end would paint the masks with gofun aleurone as well as powdered crystal and other minerals. Her job is just as important as the carvers.

The back of the masks can be just as interesting as the front. Though not painted or decorated, there is a primeval quality to it, like a cave painting. Some of these masks have an affinity with those in Canada, especially when you realize that the Sanbaso Noh dance has its origins as a prayer for a plentiful harvest, much like a rain dance. Like many Haida and Inuit mythologies, Noh’s mysteries are passed to the next generation in an oral tradition, a baton that is only secure when the sons can memorize everything without notes. The connections between these two cultures across the Pacific Rim would make a great subject of research for anthropologists and historians alike.

If you are here for an extended period of time and can speak Japanese, why not make an appointment to meet these masters and take part in the making of a mask. In this way, you can become part of the living history of Noh.