On my second business trip this week, it suddenly dawned on me that I spent more time away than at home, something that led me to think about what home really means. I was having lunch with someone in Cairns when she said that Japan was her “go to” bolthole, her place of sanctuary when everything in life is going crazy. To me, the backstreets of Kyoto are my retreat, being able to talk about life with the owners of family run stores, many set in old wooden machiya townhouses. It is these wanderings that led me to the world’s smallest ukiyo-e museum, art gallery and workshop, and of course Hokusai, who singularly transformed how Japanese wood block prints are viewed around the world.

Katsushika Hokusai was born in 1760 into a family of artisans in Edo (modern day Tokyo), and started painting from the age of six. His first job was working in a lending library, delivering books to people, and meeting people who loved books. Unlike many other countries at that time, over eighty percent of its residents were literate, with a large number of ordinary people who enjoyed reading. His portraits of these people were at the centre of Hokusai’s heart, unlike the stylised portraits in many European Neoclassical paintings focusing on nobility in the Eighteenth century. His portraits shone a light to and celebrated the uncensored moments of the ordinary person. In one of his prints depicting a moment of truth where a number of ronin were defending the name of their master, you can see in the corner of the room, a bystander half dressed scrambling to cover his body, caught unaware by this momentous occasion.

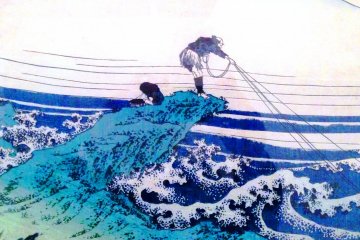

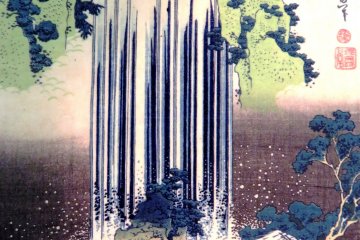

Hokusai was also an apprentice to a woodblock carver and printer, whose disciplined training can be seen in the technical excellence of his work. Every colour in a woodblock print had to be printed separately, with the block needing to be placed precisely to ensure the colours combine without smudging or distorting the image that he needed to portray. Hokusai loved landscapes, and prints such as The Care-of-the-aged Falls in Mino Province (1832) showed the exactness of his placement of the blue trees against a moss green rocky outlines of the mountain, as well its majesty compared to the tiny travellers at the bottom of the print. In many ways Hokusai was the original travel journalist and itinerant bohemian, a man without a home, having changed his name thirty times as he reinvented his work with every chapter of his life.

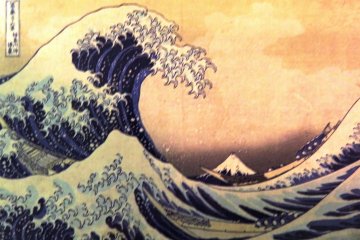

In the Edo period wood block prints were popular, and you could buy it for the same price as a bowl of noodles. Some of the prints promoted Kabuki theatre at the time, almost like movie posters. So it is sad that these days there are not so many woodblock carvers and printers left. There is a certain sense of irony that in the 21st century, images of Hokusai’s Great Wave off Kanagawa is shown in everywhere from art stores in Melbourne to subway stations in Paris, but the actual hand-made woodblock prints are as rare as hen’s teeth.

Fortunately artisans like Ichimura Mamoru, the owner of this ukiyo-e museum and studio, is trying to revive the art and technique of woodblock printing. Like Hokusai, he started his craft from a young age from his grandfather in his workshop. While he laments that he is now too old to teach apprentices, you can see him at work in this humble backstreet atelier. Living the artisan lifestyle, he distances himself from the formalised practices of the corporate world, with his museum only being open when he is awake, and closed when he is tired. So if you are here when he is around, do pay a visit and have a chat with him. Afterwards, make your way to Ezoshi Gallery, a short bicycle or bus ride away in Gion.