It can be terribly hard to make Wagashi, a Japanese sweet that complements the bitterness of Matcha in a tea ceremony. Apprentices spend years perfecting their movements using special tools, like traditional cherry wood confectionery cutters. Scientists dissect the hand movements of these experienced chefs, adding to the renewed focus these days to pass on the centuries old techniques of making Wagashi (known in Kyoto as Kyo-gashi) for future generations.

At Emi’s cooking class however, her home truths like the use of potato starch flour to stop the dough from sticking to your fingers, and using cups instead of traditional rice cake mochi moulds, have made this art form attainable even for novices. At the same time, you can feel the reverence she has for her ingredients, carefully bathing and blanching her red adzuki beans to bring out their best. “Always keep the beans under water”, she says, treating them almost like fish. It reflects her respect for the nature’s blessings. As I massaged the ingredients with her in the country-style kitchen, I felt the peace and mindfulness that usually comes with meditation.

I remember in the movie, “Lost in translation”, where Scarlett Johansson, lost and confused in Tokyo, experiences her moment of connection when she stumbled into a floral arrangement ikebana class. Like the kindly ikebana teacher in the movie, meeting Emi can be your moment of connection in a foreign land.

As befitting someone who learned from her mother rather than years of research in a university, she is softly spoken, the strict airs befitting a strict taskmaster thankfully absent. Emi is the kind of person who likes to think aloud, which I found quite endearing. It is as if there was a little girl underneath her silvery grey locks of hair. Watching her twirl her way around the kitchen table, flour scattered around the well-worn chopping boards like confetti, was almost as enjoyable as learning about cooking itself. In this country home kitchen filled with handmade ceramics, stainless steel and thousand dollar precision appliances are nowhere to be found. More like an artist’s studio, she makes Wagashi accessible to the most basic of kitchens.

Emi doesn’t have all the answers to Japanese history and botany but her love of life, family and cooking comes through in her gentle answers and advice. Her love of teaching comes through in the small comments, like, “please make the mixture a little bit harder than a pancake”, so you can easily relate to her descriptions.

In a moment of reflection, she laments that these days, if Japanese women were to go to a cooking class; they are more likely to make black forest cakes and tiramisu rather than Wagashi. It is as if they have lost their connection with their mothers. When Emi was growing up, her grandmother would make Wagashi three times a week. At the same time she is constantly reinventing her food to suit international tastes, such as the addition of strawberries to make Wagashi more accessible. However, long before Luke Mangan created salted caramels, Emi added salt to Wagashi to sharpen its sweetness.

Her cooking class, like the crescendo in a movie soundtrack, takes on a life of its own. As the aroma of the steamed cinnamon pastry encircle us, her voice takes on a musical quality, with her pitch alternating between a piano teacher and a mad scientist. “White SUGAR!” she would exclaim with a grin, like Bunsen Honeydew from the Muppet Show unveiling a secret ingredient for the very first time. But she speaks with such a kind look on her face; it is more like a child in a candy shop, rather than some crazed Dr. Jekyll coming out of his shell. Little did I realize that in times past, sugar was a rarity in Kyoto, and only the rich could afford to enjoy confectionery. To add sugar to your cooking was a sign of luxury and sophistication. It was like Emi was giving us a history lesson without knowing it.

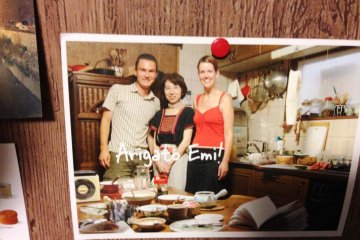

The students in her cooking class come from all ages and cultures, like a microcosm of the international tourists that you meet in Kyoto. So if there were more than four students here, the permutations of different cultural backgrounds, abilities and personalities will surely put her brain into overdrive, such is her care in tailoring every class for every student. Thankfully, her classes range from two to four students, so whether you would like to cook traditional savory or sweet Japanese foods, you are assured of a lesson that is tailored to your wishes. The thoughtful display of home-made tea cups and plates from the gallery next door completes the cultural experience.