Garden art is three-dimensional art. When we walk around a garden, touching the trees, smelling the flowers, and enjoying it from various angles, all aspects are a real pleasure. But when we look at a garden from a room, it is just like seeing a picture scroll through a window.

Experts say that if it could be defined by a painting, Konchi-in’s Tsuru-Kame Garden would correspond to the “Wind and Thunder Gods” (originally painted by Sotatsu Tawaraya) that was created at almost the same period in history. Why? One key point is that both placed a big open space between two important subjects.

Walking route

Passing through the entrance, stone pavements lead us to an outer garden by a pond. Then we are brought straight toward the inside shrine of Tosho-gu, where the hair of Tokugawa Ieyasu is enshrined. This Tosho-gu Shrine is a mausoleum where prayers are offered to Tokugawa Ieyasu (the first Shogun of the Tokugawa Shogunate) in a way similar to the great Nikko Tosho-gu Shrine. Here in Kyoto, there are stone steps that lead down to Hojo Hall behind the Tosho-gu. We then reach Tsuru-Kame Garden, which opens widely in the foreground.

Tsuru-kame Garden

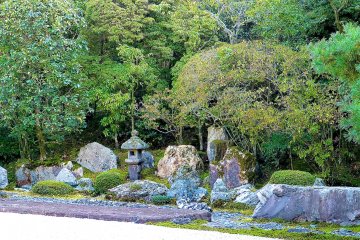

This garden was designed by Kobori Enshu (1579-1647) in around 1630, but it was a talented gardener named Kentei who directed its construction. Enshu planned the garden in minute detail, and Kentei brought it to life precisely. Enshu wanted to express the idea of a boat and/or the ocean with the white sand at the front of the garden. Viewed from a room that sits before the garden, most of the sand garden is out of sight (it's so large), and pruned trees and a group of small rocks are prominent. These trees intend to show the depths of the mountains and a deep secluded valley. A big flat stone in the center serves as a worship rock where (on special occasions) people could pray to Tosho-gu Shrine beyond the trees. Large stone groups to the right represent a crane (tsuru), and those on the left symbolize a turtle (kame). Both elements symbolize longevity and happiness. Moreover, Enshu used the idea of a one-point perspective in this garden, a concept he might have learned from knowledgeable European missionaries. A lantern in the middle of the garden plays the role of an eye stop. And the large groups of rocks on both sides, with smaller rock settings in the middle, create a great sense of depth.

Kobori Enshu and his approach to gardening

Kobori Enshu was born in 1579 into a samurai family serving preeminent regent Toyotomi Hideyoshi. At the age of 14, he started to practice Zen meditation and to learn cha-no-yu (the Way of Tea). After Hideyoshi died, he served Tokugawa Ieyasu and was then appointed to be a specialist for public constructions, including garden planning. He worked on Nikko's Tosho-gu Shrine, Kyoto's Nijo-jo Castle, Nanzen-ji’s Hojo Garden, and the Edo-jo Castle, as well as other important buildings and gardens under the Shogunate.

Enshu’s aesthetic sense is generally expressed as kirei sabi, different from the traditional concept of sabi (simple, quiet, deep, dying…) His sense of beauty was bright, elegant, and colorful. In addition, based on his classic knowledge of Japanese and Chinese literature, he put many of the newest elements brought into Japan from foreign countries into his arrangements. The essence harmonized perfectly to create his unique original world.

Enshu left a beautiful phrase showing his philosophy of cha-no-yu.

“When it snows, set a red blossom (of apricot) in a vase.”

Basically, a traditional tearoom is simple and dark. And in cha-no-yu, while guests wait for the host to enter, they enjoy looking at fittings in the very small room. The great tea master, Sen no Rikyu set out nothing on a snowy day, because he thought the snow itself would be enough. But Enshu was different. When it snowed, he thought that a red blossom would become a cordial light in the heart of his guests, who had just walked a cold narrow path to the colorless tearoom.