Matsuyama has long been a city of poetry. The feudal lord of Matsuyama was a devotee and patron of poetry, and from the Edo period onward, the city has been particularly associated with haiku, the short poetic form with three phrases of 5, 7 and 5 syllables. Matsuyama encompasses mountains, valleys, rivers and long coastlines where the seasons are reflected in everything around you. When you’re composing haiku, which requires a seasonal reference, the natural environment of Matsuyama offers an embarrassment of riches.

Matsuyama was home to the renowned haiku poet Masaoka Shiki who modernized the form, in between introducing baseball to Japan. Shiki has two museums dedicated to him, the grandiose Shiki Memorial Museum next to Dogo Park, and the humbler Shikido Museum near Matsuyama City Station.

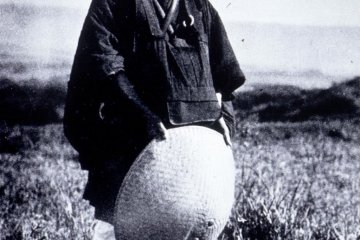

Other haiku poets who lived in Matsuyama were Kurita Chodō who built the pretty hermitage Koshin-an, and the drunken mendicant Taneda Santōka, who lived at Isso-an. The places where they composed their poems remain oases of stillness and reflection despite the bustling city around them.

Haiku are part of the fabric of Matsuyama, literally. Many of its streets are lined with stones which are carved with haiku. As you climb the steps to Matsuyama Shrine, you pass more of these stones. Kashima Island is ringed with haiku monuments. Of more immediate interest to practicing haikuists are the haiku post boxes that have been thoughtfully placed around Matsuyama. There are about 90 of them. You have to be alert to spot them, because they’re all different—the one in JR Matsuyama Station is made of bamboo. Around Dogo Onsen, there’s one built into the Honkan, and another near the foot spa is made of stone. But all of them have a little box of forms where you can write your haiku, with your name and address. Rest assured that posting a haiku isn’t like putting a message in a bottle and throwing it into the sea. Each haiku is read by a panel of haikuists, and the best of the best are published on Matsuyama City’s website, and in the Ehime Shinbun newspaper. Matsuyama cares about these things!

When you compose a haiku in English, there’s no need to adhere too strictly to the 5-7-5 pattern, which doesn’t necessarily work in English. As long as your poem is short and seasonal, all but the most grotesque pedants will recognize it as a haiku.

It’s best to visit Matsuyama and experience the haiku culture for yourself. But while you’re waiting to visit the Mecca of haiku, you can hone your skills at a distance through groups. And if you want to win a trip to Matsuyama, there’s a haiku competition to help you realize your dream.

I wonder how Shiki would have viewed international haiku competitions…