When you’re talking about the food of Matsuyama, it can be difficult to separate it from the delicious food of Ehime as a whole. Nevertheless, there are some dishes that are particularly associated with Matsuyama.

One of these helpfully bears the name of the city—matsuyamazushi (松山鮓), a kind of sushi topped with fish from the Seto Inland Sea. The rice is flavoured with both fish stock and vinegar. Another Matsuyama favourite is goshiki somen noodles (五色そうめん). These are vermicelli, coloured using natural ingredients: yellow from eggs, green from powdered green tea, brown from buckwheat flour, red from plums and shiso (a type of herb), and plain white. The somen are rolled by hand. They’re often served with tai (sea-bream), which is Ehime’s Prefectural Fish, arranged so that the fish appears to be swimming in the rippling noodles. Very cute. Tai meshi, where the fish is cooked on a bed of rice, is also found in Matsuyama. Tai-ya in Mitsu is a good place to enjoy it.

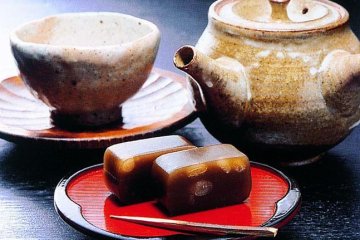

Matsuyama also has its desserts too. On first taste, traditional Japanese confections appear to lack the crucial element of sweetness required of a dessert—but persist, they grow on you. Usuzumi yōkan (薄墨羊羹) is a sort of hard jelly with white beans in it, that’s flavoured with tea. Yōkan is quite unlike any Western dessert, but it’s beautiful to look at, and it does go very well with a cup of tea at 3 pm. Botchan dango (坊っちゃん団子) are three rice dumplings on a skewer, coated with sweet bean paste colored with azuki beans, eggs and powdered green tea. No amount of explanation will convey what they’re like to eat—try them, they’re good. Perhaps the dessert that comes closest to Western ideas is the taruto, although it’s not a bit tart-like—it’s a Swiss roll, but instead of cream, it’s filled with an interesting bean paste flavoured with citrus. It goes very well with coffee or tea.

Of the foods which are found throughout Ehime, jakoten (じゃこ天) is perhaps the best well known. It’s made from a paste of juvenile fish which is fried in patties. The whole of the baby fish is used, and so the patties have a rich taste and crunchy texture. Jakoten tastes great when it’s freshly cooked, eaten hot out of a paper bag. But it’s also good cold, and it’s often sliced and used in other dishes.

Ehime is a mountainous area, and nature is never far away. If you venture into the hills around any of the towns, you’re likely to encounter wild boar and pheasants. If you’re lucky, you can find places that serve their meat. Boar is called shishi, or inoshishi (シシ、イノシシ) and pheasant is called kiji (キジ).

The Prefectural flag of Ehime features the flower of the mikan tree, any one of several types of citrus fruit. If you visit any supermarket in Ehime from early autumn to mid-summer, you can find a wide variety of local citrus fruit. The best have a wonderful balance of sweetness and acidity. My favourite are the type with a bump on the top called dekopon (sold in Australia as ‘sumo’). These are at their best in February and March.

No discussion of Japanese food would be complete without sake, the perfect complement to every kind of Japanese food. Ehime’s sake tends to be a little sweeter than other regions, although there are many dry varieties too. If you’re curious to try some sake with Japanese food, just try saying “sake” in any restaurant—help will arrive in one form or another. But there’s no better place to try sake than Kuramotoya in Matsuyama. And if you want to try a pilgrimage of 88 sake breweries around the island of Shikoku, this site is for you.

Meshi kuō! — Lets eat!