“Sankin Kotai” was a policy initiated by the Tokugawa Shogun requiring the Daimyo, or nobles to spend alternate years between their home domains, and residencies in Edo, (modern Tokyo). In principal, the practice was to provide military services to the Shogun. A set number of the daimyo’s samurai would accompany him to Edo, and while stationed there would also perform guard duties and other services to the Shogun. In reality, it was a way to impoverish the daimyo, making them spend twice as much to maintain two households, as their wives and heir were to remain in Edo as representatives, (read, hostages) and the expense of the “daimyo gyoretsu”, the lavish processions in and out of the city would prohibit them from being able to afford weapons, armor, extra samurai and from staging an insurrection.

During these processions, the daimyo would use one of the many highways, the main route being that of the Tokaido. At each of the stops were special inns reserved for the daimyo and nobility called Honjin. For commoners, the Hatago inns were to be used. Very few of these inns still remain, however the Fujikawa Juku along the Tokaido boasts one of those special few!

At it’s peak, the Fujikawa post station boasted one Honjin, a sub-honjin and 36 hatago. There were some 302 buildings in total, housing a population of 1,200. It was a bustling and lively town, catering to the frequent samurai processions as well as various travelers and pilgrims regularly coming and going.

The woodblock artist Hiroshige created a series of prints depicting a scene from each of the stops. In the works featuring the 53 stations, Hiroshige has captured one of these daimyo processions as it enters the 37th station, Fujikawa-Juku in Okazaki, Aichi Prefecture. Commoners can be seen kneeling down as the retinue enters the station, with stone walls supporting earthen mounds, and wooden notice boards posted at the entrance to the stop point.

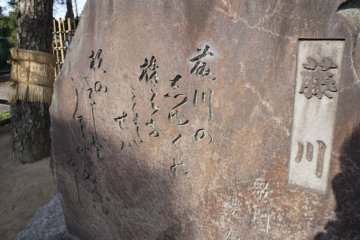

The Okazaki city government has realized the historical importance of the old post town, and has been actively trying to preserve what is left of the area. Sections of the old road have been well sign posted with granite markers, a kilometer long line of old pine trees has been preserved along the route of the old Tokaido, and a number of old structures have been saved or recreated to retain the historical atmosphere.

One such important preservation project is that of the last remaining Waki-Honjin, the sub-honjin, which now houses the Fujikawa Juku Archives Museum.

Give yourself plenty of time to explore the area, and enjoy a wander along the former Tokaido highway. See the preserved areas and stop a while at the Waki-Honjin, to get a feel for yourself of what it was like to be part of the Daimyo Gyoretsu.